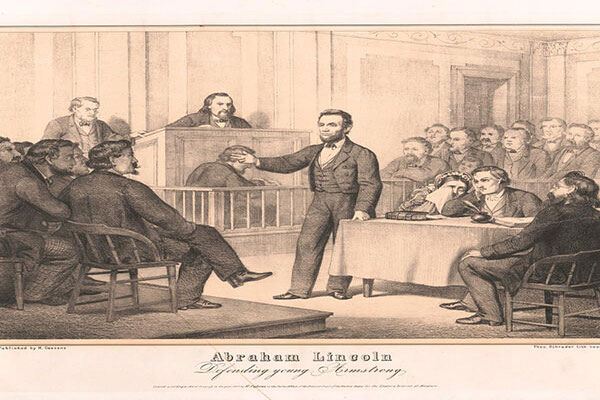

I am currently researching a journal article on the law practice of Abraham Lincoln. One of the questions that has always interested me was how his law practice shaped him as a wartime leader and president. Often ranked as our best President (although my libertarian friend Gene is lobbying for Warren Harding), I have often wondered how Mr. Lincoln’s law practice formed him and contributed to his success. And, by extension, I also wonder how the practice of family law shapes us – both as lawyers and as citizens.

In his book Lincoln the Lawyer, author Brian Dirck expounds on this subject:

Lincoln got up every morning, went to work and learned — in ways quiet yet profound — about how people interact with one another in a community, about the realities of their conflicts and abrasions, and about what he should and should not expect from the bumptious sea of humanity that crossed his path. By themselves, the cases mean little in terms of Lincoln‘s overall development; as a whole, they add up to a quarter centuries worth of lessons at the Illinois bar; lessons about the limits and feelings of human behavior, the impossibility of truly plumbing the depths of other people’s souls, and the need to find ways for communities to function without the perceived necessity of such knowledge.

– Brian Dirck

What a great quote on this theme. Think about the micro and macro of your practice. While most cases we have handled over the course of our careers are mundane and banal, cumulatively, what do they teach us?

What Are The Three Lessons Family Law Teaches Us?

1. Empathy in Family Law

For me, the practice’s greatest lesson is empathy. Human beings are frail under the best of circumstances. When you add family trauma and crisis to their lives, most respond poorly (although some certainly astonish us with their stoicism and strength). The old saying that the difference between a criminal lawyer and a divorce lawyer rings true: a criminal lawyer sees the worst kind of people on their best behavior and a divorce lawyer sees the best kind of people at their worst. We must patiently guide these troubled souls, even when they behave poorly. Often, this requires the patience of Job from the Bible. I jokingly referred to my father who happens to be a lawyer as “Gandhi” for his gentle demeanor with difficult folks. In the day-to-day rush of our practice, we must never forget our duty to serve anxious people with kindness and tolerance. Judging them is unfair – and while we sometimes joke to blow off steam–we can never make light of them or their dilemmas.

2. Humility in Family Law

Another takeaway for me is humility. Look, you’re not that great. One of my greatest life lessons was the time I won a significant case before the Illinois Supreme Court. After the ruling, I was preening about my accomplishment to anyone that would listen. The next morning my bubble burst while I was cleaning my Conure’s cage. I thought to myself, “stay humble big shot, after all, within 24 hours of the greatest achievement of your career, you’re cleaning out bird shit.” It’s hard to have an inflated ego when you are scraping bird poop off a metal cage. Every lawyer should have a birdcage to clean!

While we can occasionally influence an outcome, most of the time the outcome is out of our control. We can’t control the facts or the law, and while we can try to shape them to our advantage, we are ultimately beholden to them. Therefore, you must respect the limits of your influence. As your yardstick, judge yourself not based upon the outcome, but rather on whether you did your best under the circumstances. Keep your ego in check, do what you can do, and leave the outcome to fate. Failure to accept this fact is a prescription for an unhappy professional life.

3. Honesty in Family Law

One final lesson is the importance of honesty. As Mr. Lincoln observed in his “Notes for a Law Lecture”, “resolve to be honest at all events.” It goes without saying that we must be honest to our tribunal. But beyond that, we must also be honest to our clients, our adversaries, and, most importantly, to ourselves. The practice teaches that without integrity – without a sense of honor – the corrosive nature of family law litigation will eat you alive. It’s easy to lie to cover up a mistake, or to artificially enhance your arguments, but you’re ultimately only cheating yourself. (It reminds me of the Daniel Moynihan quote, “you’re entitled to your own opinions, but not your own facts.”) Once you start down that path, it’s hard to go back. Ultimately Judges will take note of your mendacity and your ability to persuade will become irreparably destroyed. Clients will mistrust you and your opponents will forever be on guard.

While we seem to be living in a post-truth era, ultimately truth finds a way of surfacing and spanks those who disregard it. While we all want to please our clients, you must be honest with them rather than ingratiating yourself by promising unachievable results. Better to be fired because you don’t gloss over the hard truth than being terminated later because you don’t achieve the impossible. Plus you’ll sleep better.

Goodness vs. Greatness

I dedicated my evidence book to my father who taught me, by example, that living a life of goodness is more important than striving for greatness. My practice has taught me the same lesson. I suppose he learned this lesson from his practice as well. A life in family law, while arduous, is a life well lived.

As the late great Chicago family lawyer Muller Davis observed:

Representing a child who may or may not become a complete adult, a husband who is also a father, or a wife who is also a mother, is not a transaction of the marketplace. The family lawyer is held to a higher standard. His representation is a trusteeship. His mind is bent to fairness. He steadfastly advances the cause of his client while exercising care not to destroy the other participants. He works as a craftsman whose product governs fragile relationships for substantial periods of time. The lawyer’s own concerns have no place until the case is completed. A family is at stake, and, projected from there, so is society.

– Muller Davis

What we do day to day will vibrate for generations. As a result, our careers are meaningful and purposeful. And research shows that living a purposeful life is one of the pillars of well-being. While few of us will elevate to the station of Mr. Lincoln – a true example of both goodness and greatness – at least we can use the lessons from our practice to help troubled people through the worst times of their life. And by doing so, we achieve at the highest levels.

Related Content

38 Thoughts for 38 Years Practicing Family Law

An experienced family lawyer offers 38 thoughts about the practice of family law – one for each year of his professional life.

The Top 10 Golden Rules of Argumentation

These rules will make you a better lawyer – whether arguing via Zoom, in court, or in a settlement conference in the judge’s chambers.